I've found that registers of 19th-Century births, marriages, and deaths are

online for the southern parts of Baden. These are from Standesämter that are in the Freiburg adminstrative

district. The Freiburg distict includes the purple

Kriese in the map provided.

Use these steps to find online records for your ancestors:

- Use one of these links:

- Select an Amtsgericht from the list in the left column, A listing

of its first 20 books of registry then appears in the right column.

- Select ALLE (above the slide bar on the right) to list the books that are online from the Amtsgericht.

- Find your town of interest. Several different register books may be available.

|

| Great-grandmother Leopoldina Salinger (1839-1919) |

My great-grandmother Leopoldina Salinger was born in Breisach am Rhein in 1839. Her birth on 29 May 1839 is documented in the civil registers of the city. The record is available through this online source,as well as those of her siblings Carl Julius (1833-1833), Anton Herrmann (1836-), Maria Anna Josepha (1838-), and Maria Anna (1843-).

The records of Breisach am Rhein are available in several volumes with the following groupings of years:

I have reviewed only the first and second volumes in any great detail. It is likely that records of marriages and deaths for family members after 1842 will not be in this town. Both her father Georg Salinger and mother Katherina Vogel-Salinger were born in the first decade of the 19th C, and I expect they might have deaths reported at age 65 or younger. If the siblings survived and remained in Breisach, any of their marriages would be reported at age 40 or younger.

I am pursuing further research in similar online sources for Rastatt, Ettlingen, Karlsruhe/Durlach, and Kònigheim, cities in Baden where other ancestors came from.

The Salinger Family

Revisions on 3 April 2019 update this section with more recent research.

My great-grandmother Leopoldina Salinger-Ohnsat (1839-1919) emigrated from Baden-Württemberg in 1871. Her family lived in Breisach from about 1832 to about 1842, while her father worked as an

Amtsdiener. Another family headed by Georg

Selinger lived in the outlying and smaller settlement of Hochstetten at least from 1835. Leopoldine's family name was spelled "Salinger" and occasionally "Selinger" in Germany, and its spelling "Sallinger" occurred sometime during immigration, naturalization, or resettlement.

Her parents were Georg Salinger (1803-1856) and Katherina Vogel (about 1810-1862). Georg was identified as an

Amtsdiener in several birth documents for his children. This occupation is an honorific today or a ceremonial duty that is given as a political award. In the 19th Century, an

Amtsdiener could have performed a wide variety of clerical tasks in a registrar's office or could have been little more than a manager of visitors to the office (asking citizens to wait in the lobby and escorting them to the registrar's desk when the clerk was ready to take their information). In older German usage, there may have been distinctions in the function of an

Amtsdiener, a

Büttel, a

Fronbote, a

Gerichtsdiener, and a

Saaldiener; however, modern German usage does not imply great differences, except that a

Gerichtsdiener is associated with civil and criminal courts. Simple translations could be among these: an "usher," a "beadle," or a "messenger" of a municipal court. The Zedler

Universal-Lexikon (1731-1754) has this

definition:

Amts-Knecht, Amts-Diener, ist ein geschworner Bote, welcher das, was vor Gerichte geschen soll, durch des Amtmanns Befehl denen Partheben überbringen und ankundigen muß. Wie er denn auch die Amts-Delinquenten einbringen, und dem Nachrichter überlieffern muß. [Band I (A-AM), p. 898, bottom of column 1817]

That is,

Official servant is a sworn messenger who must, at the bailiff's command, deliver to those taking part in the proceedings those charged persons who must be tried before a court of law. In the court proceedings, the Amtsdiener announces the availability of those charged. He must also bring in the charged parties and leave them with the reporter.

|

Rastatt (left), Ettlingen, and Durlach (right, top) in the

Karlsruhe region along the Rhein River |

Leopoldine's father came from

Rastatt, and her mother from

Durlach or

Ettlingen, about 80 and 90 miles north of Breisach. Both Durlach and Ettlingen are within Karlsruhe

Kreis, and Rastatt is a historically important city along the middle Rhein. Georg Salinger married Katharina Vogel on 3 December 1829 in St. Peter and Paul Catholic church in Durlach, and two children were born there: Carolina Christina in 1830 and Barbara Luise in 1831.

Although movement from one town to another within a few miles was fairly

common, the distance to Breisach seems unusual. I suspected that Georg Salinger had

performed the work of

Amtsdiener in Rastatt and was recommended for the post in Breisach. However, the marriage record for the couple states that he was "

sergeant/junior officer with the

Guards Cavalry Regiment at Gottsau." It's possible that he left military service and worked in a governmental bureau before the family moved to Breisach.

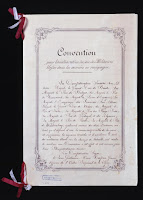

I have only preliminary research for the generation of these 2nd-great-grandparents. I have found documentation of their marriage in the registers of Durlach and Rastatt. The Rastatt register entry is a certified copy of the Durlach register:

|

Marriage registry of Georg Sallinger and Katharina Vogel,

Rastatt, Germany (two consecutive pages in the image) |

Abschrift: Auszug aus dem Trauungsbuche der katholischen Stadtpfarrei Durlach, S. 38, §5

Im Jahre tausend acht hundert neun und zwanzig den dritten Dezember nachmnittags halb zwei Uhr nach vorhergegangenen zweimaligen Aufgebothen, welche am vier und zwanzigsten Sonntag nach Pfingsten und ersten Sonntag im Advent zu Durlach und Karlsruhe geschehen sind, nach erhaltener Entlassung des Bräutigams von großherzoglich katholischen Stadtpfarramte zu Karlsruhe und nicht erhobenen Einspruche; sind von Unterzeichneten getraut und eingeseegnet worden: Georg Sallinger von Rastatt /: neuangehender Bürger von Rastatt:/, Unteroffizier vom Garde Cavallerie Regiment zu Gottsau, ehelicher Sohn des verstorbenen Sallinger Leopold von Rastatt, mit der ledigen Katharina Vogel von Ettlingen, Tochter der Katharina Vogel von hier, Ehegattin des Marand Würzburger, Schutzbürger und Leistschneider [= Leistenschneider] dahier.

Zeugen waren: die beiden Unteroffiziere: Carl Oehlwang von Karlsruhe und Stephan Bischof von Kisselbronn [= Kieselbronn] bei Pforzheim.

Durlach d. 3. Decemb. 1829. V Baumann, Pfarrer.

gegeben Durlach d. 7t. Dezember 1829 In fidem extractus: V. Baumann, Pfarrer

Zur Beglaubigung der treuen Abschrift

Rastatt d. 20t Dezember 1829

Schung, Dekan und Stadtpfarrer

Translation:

Copy: Extract from the marriage book of the Durlach Catholic town parish. Page 38, paragraph 5.

|

Marriage registry of Georg Sallinger and Katharina Vogel,

Durlach, Germany |

In the year 1829 on December 3 at 1:30 in the afternoon, after the announcement of two marriage banns that occurred on the 24th Sunday after Pentecost and the 1st Sunday of Advent in Durlach and in Karlsruhe; after receiving the release of the groom from the grand ducal Catholic town parish office in Karlsruhe, with no objections raised; were married and blessed by the undersigned: Georg Sallinger from Rastatt (prospective citizen from Rastatt.), sergeant/junior officer with the Guards Cavalry Regiment at Gottsau, legitimate son of the deceased Sallinger, Leopold from Rastatt; with the unmarried Katharina Vogel from Ettlingen, daughter of Katharina Vogel from here[ [Durlach], wife of the Würzburger Marand, legal/protected citizen and last maker here.

Witnesses were: both sergeants/junior officers Carl Oehlwang from Karlsruhe and Stephan Bischof from Kisselbronn [= Kieselbronn] near Pforzheim.Durlach,

December 3, 1829. V. Baumann, Clergyman.

Written in Durlach on December 7, 1829 Faithfully extracted: V. Baumann, Clergyman

In certification of a true/accurate copy.

Rastatt, December 20, 1829

Schung, Deacon and Town Clergyman.

Typically ages of the bride and groom are given in a marriage record, especially if they are young adults. Since the ages are not given, I presume that neither is of younger age. I guess that Georg was then about 30 years old, and that Katharina was perhaps younger than 25. So I estimated their births to be 1799 and 1807 (plus or minus 5 years), respectively. These dates establish a search range for their birth or baptism records. Recently I found Georg's birth-baptism record in Rastatt: 21 February 1803.

|

| Officers' dress uniforms of the Rastatt regimental cavalry. |

Georg Salinger's home of origin in the marriage entry is of some interest. He is given a "prospective" citizenship in Durlach; he was "release" from the "grand ducal Catholic town parish office in Karlsruhe," and his father Leopold is from Rastatt. Likely, then, Georg was born in Rastatt at the end of the 18th Century, then a city of 3000 residents. Until 1771, Rastatt was the residence of the margrave of Baden-Baden, with a large palace at the center of the city. The residence of the margrave moved in the late 18th Century to another city, but a military garrison remained in Rastatt. Perhaps the young Georg began his military service in Rastatt and was moved then to Karlsruhe to serve the grand duke. (The city was the location for peace negotiations between France, Prussia, and Austria in the last years of the 18th Century, known as the

Congrès de Rastatt. However, the negotiations had only one catastrophic result: the murder of two French diplomats and the serious wounding of a third.) I presume Georg was intending to live in Durlach, as evidenced by the parenthetical description of

neuangehender Bürger von Rastatt, "prospective citizen from Rastatt."

Katharina Vogel's home of origin in the marriage entry is also of interest. Her mother's residence is given as Durlach, but the bride's residence is given as Ettlingen. Of additional interest for research is the identity of her mother's husband as "the Würzburger Marand, legal/protected citizen and last maker here [in Durlach]."

The Georg Salinger family returned to Durlach in time for the birth of their seventh child, Maria Anna, on 29 August 1843. Because Katharina would have reached 40 soon after then, it's unlikely that more children came to the family. Georg Salinger died on 4 January 1856 in Tauberbischofsheim.

I continue research for the birth, reason for living in Ettlingen, and death of Katharina Vogel—and for information about her parents.

Leopoldine's paternal grandfather was named in her parents' marriage record: Leopold Sallinger from Rastatt. I have found the marriage of Leopold Salinger to Margaretha Mayer on 11 January 1802 in Rastatt and his death on 12 July 1821.

I estimate his birth to be around 1767; similarly, I estimate Margaretha Mayer's birth to be about 1775 and her death to have been about 1850. Her paternal great-grandparents may be Joseph Salinger (about 1745-1800) and Franziska Idamann (about 1740-1800) and Georg Mayer (about 1740-1800) married 8 August 1768 to Maria Anna Maisch (about 1760-1800).

Leopoldine's maternal grandmother was identified as Katharina Vogel from Karlsruhe-Durlach, who was married to "the Würzburger Marand, legal/protected citizen and

last maker [in Durlach]." I believe this indicates that Marand is a step-parent who came originally from

Würzburg. The mother Katharina married Morand Würzburger on 30 May 1814 in Durlach.

I estimate the elder Katharina married an unknown Vogel before 1807 in Durlach, and that she was born before 1780, probably in Durlach. However, it is possible that the younger Katharina Vogel was a birth outside of marriage (once called illegitimate). Leopoldine's maternal great grandparents may be Martin Vogel and Margaretha Wagner.